How to Work Out What To Do When You Graduate

When you leave school, the path is set out for you. When you finish your undergraduate degree, it’s not so clear.

If you’re someone who always planned on going to university, what you were going to do once you finished school was probably quite straightforward. You had to pick the five universities that would fill your UCAS application, hopefully get some offers, choose your top two among them and – if all went well – get accepted into one or the other of them. Yes, you probably made contingency plans for UCAS extra or clearing, but essentially the process whereby you figured out what you would be doing for the next three years or more had already been laid out for you. It was also a single choice: which university you went to would determine lots of other questions, like which city you would live in, and possibly what type of accommodation you might choose there, and who you would spend time with.

By comparison, the decision for what to do when you graduate is a lot tougher. You don’t have five slots to fill with your top five choices; if you’re looking to get a job, the only limit is your own tolerance for application forms and recruitment agencies. Depending on what that job is, you might be able to live almost anywhere. And your decision doesn’t need to be permanent. You might decide to take a short-term contract somewhere, conclude you don’t like it, and move somewhere else when it comes to an end.

To make things harder, alongside all these kaleidoscopic possibilities, there’s also quite a lot of pressure. Maybe one of your top career choices strongly prefers people who go into it immediately after graduation; perhaps there’s pressure from your parents to settle down; perhaps, after years of living on a student budget, you just really want to earn a salary. You may be aware that finding a job as a new graduate can be hard work. There’s the catch-22 of the need to have experience to get a job and the need to have a job to get experience. And there’s also the simple fact that there are a lot of other graduates out there that means it’s not unusual to need to send out thirty or forty job applications before you’re eventually successful. It would be hard, to say the least, to go to all that effort and only then conclude that the job is not really what you wanted in the first place.

So, in this article we look to tackle that very tricky question: how do you work out what you should do when you graduate? Here are our top tips.

Think about all the options available to you

You might think you already have a good idea of the options available to you. Let’s say you’re studying a humanities subject that doesn’t lead neatly into a particular career path, such as Philosophy. You’ve been doing a bit of tutoring to supplement the income from your student loan while at university. You might think that your options are fourfold: a graduate job, such as through a graduate scheme (e.g. the Civil Service); a non-graduate job, such as carrying on with tutoring, while you figure out what it is that you want to do; graduate study; and taking some time out for a Gap Year or similar.

It might seem that within those four options, you don’t have much choice – that it’s only really the Civil Service or perhaps somewhere like Aldi or Lidl’s management scheme that might accept you, and you’re not really interested in that kind of management; that you don’t want to do a non-graduate job for any length of time; that a Philosophy Masters is your only graduate study option; and that a Gap Year is an expensive waste of time that employers will look down on, so probably best avoided as well.

But your choices are probably much less limited than you think. Carrying on with Philosophy as an example (and noting that Philosophy probably falls into the bottom half of subjects ranked by the number of post-graduation opportunities they offer), the range of graduate jobs you might take is vast. We’ve written before about the many careers you can access with almost any degree, and there are even more that you can’t do with any degree, but where the particular subject matters less than having learned research and communications skills. There’s also no need to get cracking on that immediately. Yes, there are graduate schemes that are only available for a certain period of time after you graduate, but it’s very rare that they don’t allow you at least a year between graduation and your application.

Looking beyond the predictable

The world of non-graduate jobs should also not be so easily dismissed. For one thing, the line between a graduate and non-graduate job is a blurred one. There are plenty of roles where a degree is desired rather than essential, and others – such as tutoring – where a degree may be essential, but you possibly wouldn’t see it as a long-term career (though, of course, if you have the necessary skills to make a success of being self-employed, it can be). For another, a non-graduate job can provide a stepping-stone to a permanent, well-paid position. If you are thinking of working for a particular company, a lower-level job than you might like can be a way of getting your foot in the door.

The range of options for graduate study are also broader than many students realise. If you want to do a Masters degree, the usual requirements are that your undergraduate degree be in a closely related subject. But take the entry requirements for Oxford’s MPhil in Politics as an example – there, a ‘closely related discipline’ could be “eg. economics, history, philosophy, sociology, law, etc”. That’s not exactly restrictive. Even given this, they note that “each application will be assessed upon its own merits, and so candidates with a degree in an unrelated discipline should demonstrate the relevance of their academic background to their proposed subject or topic of study.” Beyond these options, there’s the world of conversion courses, specifically designed to enable students to transfer between different fields of study.

Finally, taking a year out is not frowned upon by employers as much as you might think. Contemplating your future career upon graduation can become quite fevered at the end of university, to the point that you might start to feel that being anything other than the perfect candidate for a role will make you unemployable. That’s very much not the case. Yes, if you spent a year romping through Thailand and all you have to show for it are some Instagram photos and a tan, that’s probably not going to impress employers that much. But if you gained something valuable by taking time out and travelling, and you can demonstrating in covering letters and interviews that it’s enhanced your understanding and value as an employee, it should be no impediment to your success.

Consider what you want to achieve

The idea of a job for life belongs to previous generations. The average person now can expect to walk several different career paths before retirement. You might start out teaching EFL, then move into foreign-language teaching in a British school, then switch to examining, then set up your own tutoring company, then work as an educational consultant – and that’s a relatively tame progression within the same field. Just as plausible is that you start off as a trainee solicitor, quit to set up your own company, get involved in local politics, take time out to have children, work for your political party when the kids are school-age and then go and run your own B&B.

All the same, starting out on one path does close off others. For instance, if you’d like to succeed in academia, especially in the sciences, a break of more than a year to do something unrelated is a significant setback. So once you’ve figured out the very broad range of options available to you, it’s time to start narrowing them down again by figuring out which ones actually appeal to you.

Some of these questions might be easy to answer. If you’d like a high salary, avoid publishing or charity work. If you want short work days and the ability to forget about your job after 5.30, becoming a social worker or a teacher is not for you. Other factors to consider are whether you’d like to live in a city or in the countryside, whether you’d like a large family (in which case you’ll need a career that’s sympathetic to you taking time off for childcare commitments) and what sort of prospects for promotion you’d like.

“Do what you love and love what you do”

But other questions are naturally harder. You might prioritise a job that makes you happy – a goal that is very difficult to quantify. There is the whole world of ‘doing what you love’; see the variety of aphorisms about how you should work out what you love most in the world, then find someone who’ll pay you to do it, or that if your work is something you love, you’ll never work a day in your life. There are a few rare and lucky souls for whom this applies, but for many people, doing what they love for eight hours a day, five days a week is a rapid recipe for falling out of love with it. Others choose careers adjacent to things that they love, such as those who go into publishing because they love books. If you’re thinking along those lines, it’s worth remembering that like most office jobs, publishing also requires a lot of budgeting and spreadsheets.

Harder still is if you want a job that will do good. The charity 80,000 Hours (based on the idea that over a lifetime, you spend 80,000 hours at work) uses utilitarian principles to determine which jobs do the most good in the world. Their results are often counter-intuitive. For instance, they argue that as there is not a shortage of people wishing to become doctors, those who prioritise doing good should look at other careers (for instance, public health), as a doctor focused on doing good and a doctor focused on their salary will save roughly the same number of lives. By contrast, earning a high salary in an ethically neutral job and donating a large percentage of it to life-saving charities saves a lot more lives, as the person who might have taken that high-earning job instead of you would probably not have donated to charity, but might have spent the cash on a big house and a Ferrari instead. Whether or not you agree with their conclusions, it’s clear that figuring out how you can do the most good in your career requires some serious thought.

Take practical steps to see which careers would suit you

You might previously have thought of things like job shadowing, work experience, internships and even short courses as things that you do not for their own sake, but to bulk up your CV. But employers don’t value experience solely because having prior experience in a field suggests you will already have the necessary skills to succeed in it. Experience is valuable also because it demonstrates that the candidate knows the kind of job they would be asked to do and liked it enough to apply for another job in it.

Why this is useful is best demonstrated by imagining the opposite – let’s say you’re an admissions tutor for a Law conversion course. The student you’re assessing studied History. They didn’t take any courses in History of Law, and nor have they provided any evidence of their interest in Law more generally; they haven’t attended supplementary courses or sought to gain any experience of what studying or practising Law is like. While a passion for Law might burn in their heart, to an admissions tutor they’re indistinguishable from someone who truly loves History, dislikes studying anything else, and only applied for Law conversion because they think it will make them more employable – i.e. not someone that tutor would want on their course.

But the same reason that this experience is valuable to an employer or admissions tutor as evidence of your interest and commitment also makes it valuable to you. Does two weeks during your summer holiday working at your local newspaper make you tired of the very concept of journalism? Does a summer course on Politics result in you buying up every related book you could find, itching to learn more? Does an internship in a science lab make you realise that the thrill of discovery doesn’t quite make up for the hard work needed to get there? Once you know what you could do and what you want to achieve, a little experience can take you from cautious to certain that you’ve found the right post-graduation path for you.

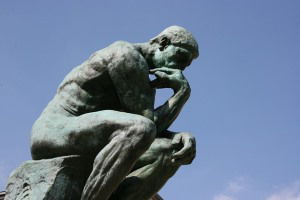

Image credits: mountain road; students graduating; multiple doors; rodin the thinker; people collaborating; thailand; clock; heart on beach; tulips